Insurance Is Not A Gambling Explain

- Gambling refers to a contract in which payment from one of the parties to the contract is definite whereas the liability/payment of the other party to the contract is indefinite. The third major aspect that renders conventional insurance impermissible is the aspect of Maysir or gambling. Insurance is definitely not a form of gambling.

- Gambling: You cannot insure your chances of losing a gambling game. Loss of profit through competition: You cannot insure your chances of winning or losing in a competition. Launching of new product: A manufacturer launching a new product cannot insure the chances of acceptability of the new product since it has not been market-tested.

Insurance Is Not Gambling Explain, turnkey casino website for sale, roulette visual basic code, craps online for free.

Help one another in virtue, righteousness and piety

5:2 The Qur'an

Islamic insurance is a term used for takaful that is a form of insurance based on principles of mutuality and co-operation, encompassing the elements of shared responsibility, joint indemnity, common interest and solidarity

What is Takaful?

All human activities are subject to risk of loss from unforeseen events. To alleviate this burden to individuals, what we now call insurance has existed since at least 215 BC. This concept has been practiced in various forms for over 1400 years. It originates from the Arabic word Kafalah, which means 'guaranteeing each other' or 'joint guarantee'. The concept is in line with the principles of compensation and shared responsibilities among the community.

Takaful originated within the ancient Arab tribes as a pooled liability that obliged those who committed offences against members of a different tribe to pay compensation to the victims or their heirs. This principle later extended to many walks of life, including sea trade, in which participants contributed to a fund to cover anyone in a group who suffered mishaps on sea voyages.

In modern-day conventional insurance, the insurance vendor (the insurance company) sells policies and invests the proceeds for the profit of its shareholders, who are not necessarily policyholders. There is therefore a clear disjunction between policyholders and shareholders. Payouts to policyholders may vary depending on financial performance, but a minimum positive return is always contractually guaranteed.

Takaful is commonly referred to as Islamic insurance; this is due to the apparent similarity between the contract of kafalah (guarantee) and that of insurance.

However, takaful is founded on the cooperative principle and on the principle of separation between the funds and operations of shareholders, thus passing the ownership of the Takaful (Insurance) fund and operations to the policyholders. Muslim jurists conclude that insurance in Islam should be based on principles of mutuality and co-operation, encompassing the elements of shared responsibility, joint indemnity, common interest and solidarity.

In takaful, the policyholders are joint investors with the insurance vendor (the takaful operator), who acts as a mudarib – a manager or an entrepreneurial agent for the policyholders. The policyholders share in the investment pool's profits as well as its losses. A positive return on policies is not legally guaranteed, as any fixed profit guarantee would be akin to receiving interest and offend the prohibition against riba.

For some time conventional insurance was considered to be incompatible with the Shari’ah that prohibit excessive uncertainty in dealings and investment in interest-bearing assets; both are inherent factors in conventional insurance business.

However, takaful complies with the Shari’ah (which outlines the principles of compensation and shared responsibilities among the community) and has been approved by Muslim scholars. There is now general, health and family (life) takaful plans available for the Muslim communities.

Prohibitions of Gharar, Maysir and Riba

Gharar: An insurance contract contains gharar because, when a claim is not made, one party (insurance company) may acquire all the profits (premium) gained whereas the other party (participant) may not obtain any profit whatsoever. Ibn Taimiyah, a leading Muslim scholar, further reasoned 'Gharar found in the contract exists because one party acquired profit while the other party did not'. The prohibition on gharar would require all investment gains and losses to eventually be apportioned in order to avoid excessive uncertainty with respect to a return on the policyholder's investment.

Maysir: Islamic scholars have stated that maysir (gambling) and gharar are inter-related. Where there are elements of gharar, elements of maysir is usually present. Maysir exists in an insurance contract when; the policy holder contributes a small amount of premium in the hope to gain a larger sum; the policy holder loses the money paid for the premium when the event that has been insured for does not occur; the company will be in deficit if the claims are higher that the amount contributed by the policy holders.

Riba: Conventional endowment insurance policies promising a contractually-guaranteed payment, hence offends the riba prohibition. The element of riba also exists in the profit of investments used for the payment of policyholders’ claims by the conventional insurance companies. This is because most of the insurance funds are invested by them in financial instruments such as bonds and stacks which may contain elements of Riba.

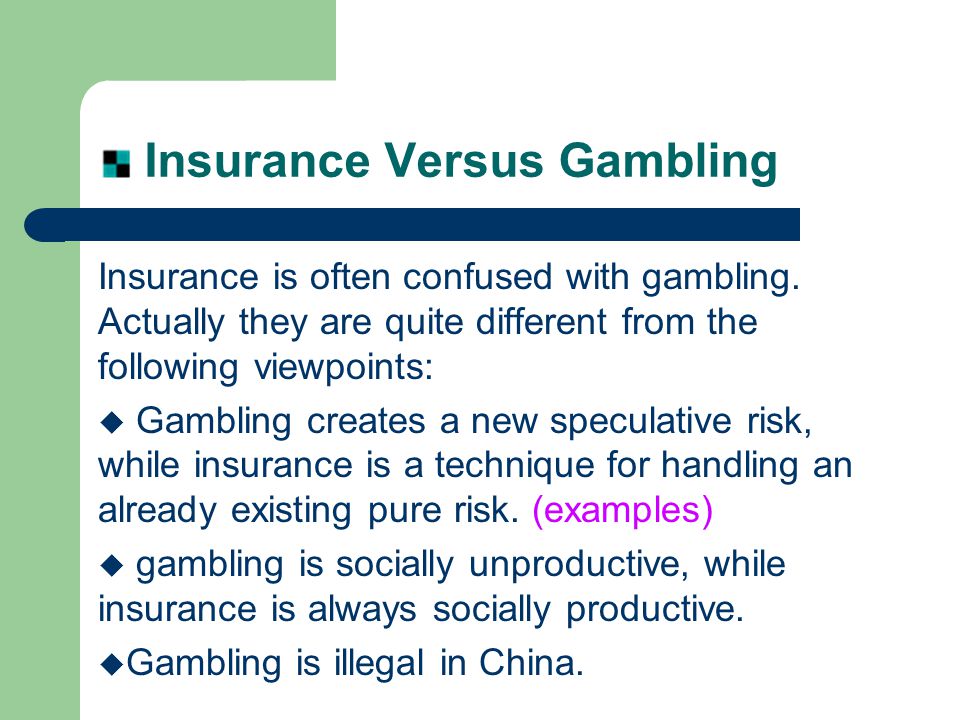

Gambling and Insurance

Gambling and insurance are two distinct and different operations. Gambling is speculative in its risk assessment whereas insurance is a pure risk and is non-speculative. In gambling, one may win or lose by creating that risk. In insurance, the risk is already there and one is trying to minimise the financial effects of that risk. Insurance shifts the impact of that risk to someone else and relieves the person of risk. The risk nevertheless still remains.

While gambling promotes dissension, ruin and hatred, insurance based on cooperative principles, enables the insured to lessen the financial impact without which it could drive the individual and his dependents to poverty, thereby weakening their place in the society. There is nothing in Islam that prevents individuals from making a provision for their dependents. Seen collectively for large groups of insured population, insurance strengthens the financial base of the society.

Islamic scholar, Yusuf Ali, in his translation of The Holy Qur’an, comments on Sura (chapter) Al-Baqara, ayat (verse) 219, 'Insurance is not gambling, when conducted on business principles. Here the basis for calculation is statistics on a large scale, from which mere chance is eliminated. The insurers charge premium in proportion to the risks, exactly and scientifically calculated'.

Basis and Principles of Takaful

Islamic insurance requires each participant to contribute into a fund that is used to support one another with each participant contributing sufficient amounts to cover expected claims.

The underlying principles of Takaful may be summarised as follows:

- Policyholders co-operate among themselves for their common good.

- Every policyholder pays a part of the contribution as a donation to help those that need assistance.

- Losses are divided and liabilities spread according to the community pooling system.

- Uncertainty is eliminated in respect of subscription and compensation.

- It does not seek to derive advantage at the cost of others.

Theoretically, Takaful is perceived as cooperative insurance, where members contribute a certain sum of money to a common pool. The purpose of this system is not profits but to uphold the principle of 'bear ye one another's burden.'

Why No to Conventional Insurance

In modern business, one of the ways to reduce the risk of loss due to misfortunes is through insurance. The concept of insurance where resources are pooled to help the needy does not necessarily contradict Islamic principles.

Three important differences distinguish conventional insurance from Takaful:

- Conventional insurance involves the elements of excessive uncertainty (gharar) in the contract of insurance;

- Gambling (maysir) as the consequences of the presence of excessive uncertainty that rely on future outcomes

- Interest (riba) in the investment activities of the conventional insurance companies;

- Conventional insurance companies are motivated by the desire for profit for the shareholders;

- Conventional system of insurance can be subject to exploitation. For example, it is possible to charge high premium (especially in monopolistic situations) with the full benefit of such over-pricing going to the company.

The key difference between Takaful and conventional insurance rests in the way the risk is assessed and handled, as well as how the Takaful fund is managed. Further differences are also present in the relationship between the operator (under conventional insurance using the term: insurer) and the participants (under conventional it is the insured or the assured). Takaful business is also different from the conventional insurance in which the policyholders, rather than the shareholders, solely benefit from the profits generated from the Takaful and Investment assets.

How does Takaful Work

All participants (policyholders) agree to guarantee each other and, instead of paying premiums, they make contributions to a mutual fund, or pool. The pool of collected contributions creates the Takaful fund.

The amount of contribution that each participant makes is based on the type of cover they require, and on their personal circumstances. As in conventional insurance, the policy (Takaful Contract) specifies the nature of the risk and period of cover.

The Takaful fund is managed and administered on behalf of the participants by a Takaful Operator who charges an agreed fee to cover costs. These costs include the costs of sales and marketing, underwriting, and claims management.

Any claims made by participants are paid out of the Takaful fund and any remaining surpluses, after making provisions for likely cost of future claims and other reserves, belong to the participants in the fund, and not the Takaful Operator, and may be distributed to the participants in the form of cash dividends or distributions, alternatively in reduction in future contributions.

Operating Principles

An Islamic insurance company must have the following operating principles:

- It must operate according to Islamic co-operative principles.

- Reinsurance commission may be paid to, or received from, only Islamic insurance and reinsurance companies.

- The insurance company must maintain two funds: a participants/policyholders' fund and a shareholders' fund.

The Policyholders' Fund

- The assets of the policyholders' fund consist of:

- Insurance premiums received

- Claims received from re-insurers

- Such proportion of the investment profits attributable to policyholders as may be allocated to them by the Board of Directors.

- Salvages and recoveries

- Consultancy and other receipts.

- All the claims payable to the policyholders, reinsurance costs, technical reserves, administrative expenses, etc., excluding the expenses of the investment department, shall be met out of the policyholders' fund.

- The balance standing to the credit of the policyholders' fund at the end of the year represents their surplus. The General Assembly may allocate the whole or part of the surplus to the policyholders' special reserves. If a part, the balance will be distributed among the policyholders.

- When the policyholders' funds are insufficient to meet their expenses, the deficit is funded from the shareholders' fund.

- The shareholders undertake to discharge all the contractual liabilities of the policyholders' fund, but this liability does not exceed their equity in the company.

The Shareholders' Fund

- The assets of the shareholders' fund consist of:

- Paid-up capital and reserves attributable to shareholders

- Profit on the investment of capital and shareholders' reserves

- Such proportion of the investment profit generated by the investment of the policyholders' fund and technical and other reserves as is attributable to them

- Miscellaneous receipts

- All the administrative expenses of the investment department are deducted from the Shareholders' Fund.

- The balance of the shareholders' surplus, if any, is distributed among them.

Investment of Funds

The company may invest its funds only on a profit-and-loss-sharing basis, as approved by the Shari'ah.

Products and Services Offered by Islamic Insurance Companies

Islamic insurance companies may offer competitively priced products, without curtailing the scope and benefit of insurance coverage made traditionally available to the public by conventional insurance companies.

As regards life insurance facilities, Islamic insurance companies have developed Islamic Trust Funds for social sol idarity, mortgage protection, student protection and employers' protection.

Models of Takaful

There are various models of takaful according to the nature of the relationship between the company and the participants. There are wakalah (agency), mudarabah and a combination of the two. In the Sudanese takaful model, every policyholder is a shareholder in it. An Operator runs the business on behalf of the participants and no separate entity manages the business. Shari'ah experts consider this preferable. In other Islamic countries, the legal framework does not allow this arrangement and takaful companies work as separate entities on the basis of mudarabah (in Malaysia) and wakalah (in the Middle East).

In the mudarabah model practised mainly in the Asia Pacific region, the policyholders receive any available profit on their part of the funds only. The Shari'ah committee of a takaful company approves the sharing ratio for each year in advance, most of the expenses being charged to the shareholders.

In the wakalah model, the surplus of policyholders' investments – net of the management fee or expenses - goes to the policyholders. The shareholders charge the wakalah fee from contributions and this covers most of the expenses of the business. The fee is fixed annually in advance in consultation with the company's Shari'ah Supervisory Board. The management fee is related to performance.

Differences between Takaful and Conventional Insurance

The overwhelming majority of Islamic jurists have concluded that the conventional insurance contract is unacceptable to Islam, not being in conformity with the Shari'ah for the following main reasons:

- it includes an element of al-gharar (uncertainty)

- it is based on the theory and practice of interest; a conventional life insurance policy is based on interest, while an Islamic model is based on tabarru where a part of the contributions by participants are treated as donation. For this reason, policy holders in takaful are usually referred to as participants.

- it is a form of gambling.

First and foremost, Islamic insurance, in conformance with the Islamic Shari'ah, is a form of social solidarity (takaful), based on the principles of trusteeship and co-operation.

- In conventional insurance, the insured substitutes certainty for uncertainty. In return for a predetermined payment, the premium, he/she transfers to the insurer the possible economic losses from stipulated risks. In Islamic insurance, the participants share all risks mutually and no transfer of risk is involved.

- Conventional insurance companies are motivated by the desire for profit, while Islamic insurance companies are non-profit making, the shareholders not being entitled to share in the profits of the business although they are entitled to charge fees for their services and share in the investment returns of funds managed by them

- The policy-holders in a conventional insurance company have no right to vote in the elections of the directors of the company or to see the annual accounts of the company, while in Islamic companies; these facilities are available to all participants who pay a certain stipulated amount of premiums (contributions).

- In the takaful system, if the assured dies before the policy matures, the beneficiary is entitled to the whole amount of the premiums, the bonus and dividend and a share of the profits made over the paid premiums, plus a donation from the company out of the participants/policy-holder's contributions given on the basis of tabarru. Such a transaction is seen as a mutual contribution towards the welfare of the helpless in society. Where the insured is still alive on the maturing of the policy, he/she is entitled to the whole amount of the premiums, a share of the profit made over the premiums, a bonus and dividends according to the company policy.

- In a conventional life insurance policy, the agent's payments are paid out of the insured's paid premiums, whereas in the Islamic model, the agents work for the company and thus are paid by the company.

- The insurable interest in the conventional system is usually paid to the policyholder, if he/she is alive at the expiry of the policy. If he/she dies before that date, the insurable interest is paid to the beneficiaries, who may include including family, servants, company, trustee, partners, mortgagor, etc. But under the Islamic model, the insurable interest goes to the assured or his/her heirs, according to the principles of Mirth or Wasiyyah.

Co-operative Insurance

The concept of co-operative insurance is acceptable in Islam because:

- The policyholders co-operate actively for their common good;

- Every policyholder pays his subscription in order to help those who need it;

- It spreads liability in the community by a pooling system;

- It does not aim at deriving undue advantage for one at the cost of other individuals;

- The element of uncertainty is eliminated as far as determination of the premiums is concerned.

An Islamic co-operative insurance contract should embody the following conditions:

- The company functions according to Islamic co-operative principles.

- The policyholders have the right to participate in surplus profits and are liable to contribute additional amounts if their subscriptions are not sufficient to meet all the losses. However, it is preferable for such losses to be written off against future surpluses. Shareholders are not entitled to any of the underwriting profits generated by the insurance operations. But, as mudarib (agents), they are entitled to receive a proportion of the profits from the investment of insurance funds, plus, of course, all the profits on the investment of their own capital and any other funds and reserves attributable to them.

- The company will strictly follow Islamic laws in the matter of investment and will not indulge in the practice of usury.

- Policyholders are represented on the Board of Directors and have a right to scrutinise its accounts.

Gambling and Insurance

There are three main differences between a gambling contract and an insurance contract.

- In a gambling contract, neither party has any other interest than winning a sum of money. The gambler is not being indemnified against any loss. But, in an insurance contract, the insured's right to be paid depends on his suffering loss from the insured peril. In other words, an insurance contract is a contract of indemnity, which is non-existent in a gambling contract.

- In the case of gambling, one party must win and the other loses. In insurance, on the other hand, the event entitling the insured to compensation may or may not happen during the period of the policy, but he pays a premium for being protected during that time.

- If a gambler wins, he gets back not only his original stake but also an additional amount without suffering any loss, whereas an insured person never gets back his premium and is only indemnified to the extent that he has suffered damage.

Pricing Transactions linked to Interest-rate Benchmark

There are continuing debates on whether the spirit of Shari`ah is being violated by the practice of 'benchmarking' linked interest rate benchmark such as London Interbank Offered rate (LIBOR) plus an agreed mark-up in also pricing returns on Islamic finance transactions . At a very fundamental level, the reason for the debates is the lack of understanding to clearly discern the difference between the use of LIBOR as a benchmark for pricing and the use of non-Shari’ah compliant assets as a determinant for returns.

However, benchmarking touches upon the integrity of Islamic Finance as a whole, and the concept of Shari’ah-compliance vs Shari’ah-based approach in particular. There are practical challenges delaying a switch to participation-based structures, such as Musharakah and Mudarabah, that require financiers to participate in the underlying asset in a financing transaction.

Retakaful or Reinsurance

Frequently, the scale of insurance risks underwritten is too great for one insurer to carry safely. In these circumstances, companies use reinsurance to mitigate their own risk exposure. When insurers insure a risk again with another company, it is called reinsurance which allows the insurance industry to spread its losses, lessening the impact of claims on any one company.

Most insurance companies have to spread their liabilities among other insurance companies, which are called reinsurance companies. The reinsurance contract, for Islamic companies, must be contracted in conformity with the Shari'ah.

There is currently a shortage of retakaful capacity and the lack of companies in the market presents a challenge as well as an opportunity. The challenge is to have a large enough takaful market to justify retakaful business. There is also a global need for strong and credible retakaful operators to assist the growth and expansion of takaful business. Shari’ah scholars have allowed takaful operators to reinsure conventionally when no retakaful alternative is available, although retakaful is strongly preferred.

However, this conventional reinsurance represents a dilemma, as it is contrary to the customer’s preference of seeking cover on Islamic principles. Structurally retakaful operating principles are similar to the takaful operating principles, and the same Shari’ah principles apply.

Preference must be given to Islamic reinsurance companies. The aim should be to end relations with conventional commercial reinsurance companies as soon as possible.

Shari'ah Authenticity

Shaikh Yusuf Talal DeLorenzo, Islamic scholar, position is that unless a financial product or service can be certified as Shari’ah compliant by a competent Shari’ah supervisory board, that product's authenticity is dubious. At that point, it will be the responsibility of the individual investor or consumer to determine on his or her own that the product complies with the principles and precepts of the Shari’ah.

Shari'ah Supervisory Board [Religious Board]

The role of Shari’ah Supervisory Board members is to review the takaful / retakaful operations, supervise its development of Islamic insurance products, and determine the Shari’ah compliance of these products and the investments. The Shari’ah Supervisory Board have to carry their own independent audit and certify that nothing relating to any of the operations involve any element that is prohibited by Shari’ah.

Islamic financial institutions must adhere to the best practices of corporate governance however they have one extra layer of supervision in the form of religious boards. The religious boards have both supervisory and consultative functions. Since the Shari’h scholars on the religious boards carry great responsibility, it is important that only high calibre scholars are appointed to the religious boards.

An Islamic financial institution is required to establish operating procedures to ensure that no form of investment or business activity is undertaken that has not been approved in advance by the religious board. The management is also required to periodically report and certify to the religious board that the actual investments and business activities undertaken by the institution conform to forms previously approved by the religious board.

Islamic financial institutions that offer products and services conforming to Islamic principles must, therefore, be governed by a religious board that act as an independent Shari’ah Supervisory Board comprising of at least three Shari’ah scholars with specialised knowledge of the Islamic laws for transacting, fiqh al mu`amalat, in addition to knowledge of modern business, finance and economics.

They are responsible primarily to give approval that banking and other financial products and services offered comply with the Shari’ah and subsequent verification that of the operations and activities of the financial institutions have complied with the Shari’ah principles (a form of post Shari’ah audit). The Shari’ah Supervisory Board is required to issue independently a certificate of Shari’ah compliance.

The day-to-day application of Shari’ah by the Shari’ah Supervisory Boards is two-fold. First, in the increasingly complex and sophisticated world of modern finance they endeavours to answer the question on whether or not proposals for new transactions or products conform to the Shari’ah. Second, they act to a large extent in an investigatory role in reviewing the operations of the financial institution to ensure that they comply with the Shari’ah.

The concept of collective decision-making, in other words, decisions made by more than one scholar, is especially important. Shari’ah Supervisory Boards function is to ensure that decisions are not unilateral, and that difficult issues of finance receive adequate consideration by a number of qualified people.

Shaikh Yusuf Talal DeLorenzo, Islamic scholar, position is that unless a financial product or service can be certified as Shari’ah compliant by a competent Shari’ah supervisory board, that product's authenticity is dubious. At that point, it will be the responsibility of the individual investor or consumer to determine on his or her own that the product complies with the principles and precepts of the Shari’ah.

Status of Takaful

As Islamic finance continues to expand, there is likely to be a huge takeoff of other products such as pensions, education, marriage and health Takaful plans. There is also a huge scope for mortgage Takaful.

Islamic principles strong emphasis in Takaful on the economic, ethical, moral and social dimensions, to enhance equality and fairness for the good of society as a whole should also have appeal for the ethically minded.

In modern society, insurance has become a necessity to trade and industry. Life insurance has become the most effective vehicle for mobilising savings, for capital formation and for long-term investment, as well as for making provision for old age and bereavement in the case of individuals.

In the west, the insurance sector is the largest single contributor to the capital market. Banks and insurance companies now form international alliances for mutual benefit.

There is an increasing demand for a Shari'ah-compliant insurance system. Until recently, there has been a low demand for insurance in Islamic countries, because Muslims believe that insurance is un-Islamic. The development of Islamic insurance, therefore, requires extensive education of the Muslim public, besides development of resources and expertise, a legal framework for it, the harmonization of practices, development of new Shari'ah-compliant instruments, accounting standards, and arrangements for retakaful.

Links

Links on this page are provided to sites of organisations with whom IIBI had entered into Memorandum of Understanding for collaboration and cooperation and other sites that IIBI considers important, such as government ministries, central banks, agencies and organisations as well as standard setting bodies and any particular individual concerned with Islamic banking and Islamic insurance related matters. IIBI is not responsible for the content on sites linked through this page.

Collaboration and Cooperation [TODO: create link]

Links to Other Sites [TODO: create link]

Articles

Articles and presentations below are by eminent scholars and practitioners in the field Takaful. You may search for more information on takaful on the Institute's NEWHORIZON magazine website at www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

- Takaful Industry: Global Profile and Trends, 2001

By Mohammad Ajmal Bhatty

Chief Executive, Takaful International, Bahrain

- An Overview of the Takaful Industry

By Dato' Mohd Fadzli Yusof

Chief Executive Officer, Sharikat Takaful, Malaysia

- Tomorrow's Takaful Products

By Ikram Shakir

- Building a Comprehensive Islamic Financial System: New Financial Opportunities

Key note address delivered by Governor of Bank Negara Malaysia, Tan Sri Dato' Sri Dr. Zeti Akhtar Aziz's organised by the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance's International Conference on Islamic Insurance

Shari'ah Ruling

In practice, the permissibility or otherwise of a transaction or business activity is governed by the Shari'ah, that provides the framework for a set of rules and laws, governing economic, social, political, and cultural aspects of Islamic societies.

The rules governing Islamic Finance are derived from the Shari'ah. The Shari'ah is a framework of Islamic Jurisprudence derived from the primary sources: The Qur'an and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) known as the Sunnah. In addition to which there is a dynamic secondary source of common law rulings and scholarly interpretations referred to as Fatwa's. These fatwas are the results of human interpretation of the Shari' ah, of its texts, or its principles, or a combination of the two; they are not the word of God. Islamic law, it must be remembered, is more a process than a code, and the results of legal deliberations may differ when different methods are employed. Several fatwas are indicative of an acceptance on the part of Shari'ah Supervisory Boards of new realities in the marketplace and of their willingness to understand and work with these to the extent that Islamic religious and legal principles will allow. Such an attitude has ever characterized the best in Islamic legal thought.

MODERN CONVENTIONAL BANKING

The originators of modern banking based their system on ‘interest-oriented investments and earnings which are clearly prohibited in the Shari'ah of Islam. Therefore, modern banking institutions, which gradually became essential to the commercial activity of the entire world, were totally antithetical to the guidance revealed to humankind through the Qur'an and the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh).

Many Muslims, believing in the prohibition of interest, remained aloof from this modern system of banking, and those who did enter the field restricted themselves to the routine work necessary for their employment. This was done because they had reservations about interest-based transactions and also because, owing to their political decline, they were unable to control the wheel of international commercial transactions.

RULES OF ISLAMIC FINANCE

The rules of Islamic finance adhere to the broad principles of avoiding Maysir and Qimar which are gambling and speculation along with Gharar which is uncertainty coupled with exploitation and unfairness. This closes the door to the concept of interest and precludes the use of conventional debt-based instruments. The Islamic financial system encourages risk-sharing, promotes entrepreneurship, discourages speculative behavior, and emphasises the sanctity of contracts.

The central tenet of the Islamic financial system is the prohibition of Riba, a term literally meaning 'an excess' and interpreted as 'any unjustifiable increase of capital whether in loans or sales'. More precisely, any guaranteed increase in return tied to the maturity and the amount of principal, regardless of the performance of the investment, would be considered riba and is strictly prohibited.

Islamic finance offers different instruments to satisfy providers and users of funds in a variety of ways. Basic instruments include cost-plus markup financing (murabaha), profit-sharing (mudarabah), leasing (ijarah), partnership (musharakah), and forward sale (bai' salam). These instruments serve as the basic building blocks for developing a wide array of more complex financial instruments, suggesting that there is great potential for financial innovation and expansion in Islamic financial markets

The Islamic scholars and Shari'ah Supervisory Boards of different Islamic financial institutions have passed a large number of resolutions through collective ijtihad interpreting the basic principles underlying Islamic transactions and the requirements of the Shari'ah with regard to different modes of financing, as well as some details of their practical implementation. This understanding is necessary to facilitate not only their compliance with the Shari' ah, but also helps Islamic financial institutions to use the new products in the light of Islamic principles.

If an Islamic financial institution is not in compliance with Shari'ah precepts, there is nothing but its name to distinguish it from a conventional institution. One of the goals in publishing this work is to enhance the appreciation of practioners for the importance of Shari'ah compliance and its significance for consumers.

The bedrock of Islamic banking is the Shari'ah law enshrined in the Qur'an and the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). Unfortunately there is an impression in certain quarters, especially in the West, that there is no agreement among the Shari'ah scholars on what actually constitutes Islamic banking. Late Sir Edward George, Governor of the Bank of England highlighted this impression, in address to a recent conference on Islamic Banking. He said,

There are a number of issues that we need to address. One is that, as I understand it, there is no single definition of what constitutes Islamic banking. Different institutions interpret the acceptability of Islamic banking products in their own way. Individual boards of Shari'ah advisers apparently have equal authority, so that in some jurisdictions there is no definitive answer as to the status of a particular Islamic banking product. This leads to uncertainty about what is, and what is not, the ‘acceptable' way to do a particular business, which in turn can complicate assessment of risk both for the bank and its customers.

Rather, it will be seen by the involvement of Shari'ah scholars that they are quite definitive, and in agreement, on what constitutes Islamic banking. The minor differences of opinion, if and when they exist, relate to matters of procedure or detail, but not to substance. Such differences are common among judges in courts of law throughout the world.

SHARI'AH GUIDING PRINCIPLES

Insurance Is Not A Gambling Explained

The Shari’ah has evolved within the guidelines set by three broad principles agreed upon by Islamic scholars and jurists over the centuries. These are:

- Interest of the community takes precedence over the interests of the individual;

- Relieving hardship takes precedence over promoting benefit;

- A bigger loss cannot be prescribed to alleviate a smaller loss and a bigger benefit takes precedence over a smaller one. Conversely a smaller harm can be prescribed to avoid a bigger harm and a smaller benefit canbe dispensed with in preference to a bigger one.

SHARI'AH SUPERVISORY BOARDS

Introduction by (Ret'd) Justice Muhammad Taqi Uthmani, International Shari'ah Scholar

Compendium of Legal Opinions Volume I

Published by the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance, London

Modern banking developed in an era that witnessed the political decline of the Muslim Ummab throughout the world. The originators of modern banking based their system on ‘interest-oriented investments and earnings which are clearly prohibited in the Shari'ah of Islam. Therefore, modern banking institutions, which gradually became essential to the commercial activity of the entire world, were totally antithetical to the guidance revealed to humankind through the Qur'an and the Sunnah of the Prophet, upon him be peace and blessings.

Many Muslims, believing in the prohibition of interest, remained aloof from this modern system of banking, and those who did enter the field restricted themselves to the routine work necessary for their employment. This was done because they had reservations about interest-based transactions and also because, owing to their political decline, they were unable to control the wheel of international commercial transactions.

Since the acquisition of political freedom by many Muslim countries during the past thirty years, it has been the cherished dream of the Muslim Ummah to develop a new banking system based on Islamic principles. Unfortunately, the political authorities of the Muslim countries paid precious little if any attention to bringing their socio-economic activities into harmony with the principles of the Shari'ah. Hence, certain groups of Muslims individuals were forced to establish Islamic banking institutions on their own, and without any meaningful support from their governments. Several Islamic banks were established in the decade of the Seventies and through them the cherished dream of Islamic banking was translated into reality, at least at the private level.

From the very beginning, Islamic banking institutions have been constantly guided by Religious scholars on their respective Shari'ah Supervisory Boards who are responsible for designing their transactions in accordance with the principles of the Shari'ah and subsequently keeping a watchful eye over their operations. These boards have devised new modes of financing to replace interest-based transactions. The management of an Islamic banking institution brings its day to day problems before its Board which, after examining the relevant details, will decide whether or not the proposed transactions are in line with Shari'ah principles. Such decisions by the Boards are called fatwas.

The function of a Shari'ah Supervisory Board is of a very delicate nature. On the one hand, they are meant to abide strictly by Islamic principles, and on the other they have to fulfill the requirements of the constantly emerging needs of the contemporary marketplace. The task entrusted to the Shari'ah boards is indeed a difficult one; because when we claim that Islam provides solutions to the problems of every time and place, it does not mean that Islam has given a specific rule for each and every minute detail of every transaction.

In fact, the sacred sources of the Shari' ah, the Qur'an and the Sunnah, have provided Muslims with a set of eternal principles, but their application to the practical situations of each age requires the exercise of ijtihad. This means consultations in which the individual deliberations of many scholars play a vital role in reaching many firm conclusions. This exercise sometimes brings different answers from different Shari'ah Supervisory Boards with regard to the same question. The Shari' ah Supervisory Boards, being comprised of a number of Islamic scholars, decide the matter placed before them after mutual deliberations, which is tantamount to collective ijtihad.

RESOLUTION OF THE ISLAMIC FIQH ACADEMY

The Islamic Fiqh Academy, constituted under the auspices of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) represented by all its member countries, in its Second Session held at Jeddah during December 22-28, 1985 adopted a resolution which, inter alia, provided:

Any excess or profit on a loan for a deferred payment when the borrower is unable to repay it after the fixed period and similarly any excess or profit on a loan at the time of contract are both forbidden as riba in the Shari' ah.

Alternative banks should be established according to the injunctions of Islam to provide economic facilities.

The Academy resolves to request all Islamic countries to establish banks on Shari'ah principles to fulfill all the requirements of a Muslim according to his beliefs so that he may not face any repugnance.

COMPENDIUM OF LEGAL OPINIONS

Edited and Translated by Yusuf Talal DeLorenzo, Independent Shari'ah Scholar Director, Master's Program for Imams

Insurance Is Not A Gambling Explaining

The Graduate School of Islamic and Social Sciences, Leesburg, Virginia USA

Published by the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance, London

Extract from Translator's Introduction - Volume I

If the numbers indicate anything about Islamic banking, it is that an exciting chapter in the religious, cultural, and intellectual life of Muslims is opening. The relatively new field of Islamic economics and banking is particularly challenging for the reason that it brings together scholarship from jurists and economists. Realistically speaking, however, there is much about this novel interdisciplinary field that is not well understood, even at the conceptual level; and a great deal of groundwork still needs to be done. The problem at the present time, if we seek to reduce the matter to its lowest common denominator, is that scholars from both fields bring their own intellectual and disciplinary predilections to their understanding of the new phenomenon, and these are often at ideological and even paradigmatic loggerheads with one another. For example, many Muslim jurists are reluctant to exercise any sort of independent thinking on economic issues, preferring instead to rely on the scholarship of past ages. Thus, their response to new questions is to locate in the classical legal literature questions of a similar nature, through the liberal use of what may at best be termed “rough” analogy, and then to ‘graft the old solutions prescribed there to the questions at hand.2 In contrast to the literalist and traditionalist orientations of many Muslim jurists, our economists have suffered from a lack of Islamic contributions to their field. A former official of the State Bank of Pakistan asserts that Muslims writing on economics often apply western standards in proposing their “Islamic” models. “Let us admit that we Muslims are oriented in western theories of economics and are apt to believe them to be a fair standard of judging policies and decisions.”3 Moreover, in their inability to appreciate Shari'ah principles and purposes, many Muslim economists appear in their thinking to assume that the only purpose of fiqh is to regulate and facilitate economic activity. At a very fundamental level, they would endow homo Islamicus with the same traits as the neoclassical homo economicus whose primary motivation is utility and precious little else.

In modern times the appearance of serious thought, from an Islamic perspective, on the subject of economics coincided closely with the emergence of Muslim nation states following the colonial experience, at a time when Muslims sought not only to repair their ailing economies, but to reestablish their cultural and religious identities. Gradually, the ideas generated by this preliminary thinking led some Muslims to speak in terms of “Islamic Economics,” and a respectable body of literature on the subject (however tentative) was developed in several different languages, especially in Arabic, English, Persian, and Urdu, with significant contributions by both Muslim economists and jurists. Clearly, these works contributed to the establishment of Islamic banks as the most immediately implementable manifestation of the desire on the part of Muslims for working models of an “Islamic” economic system. The success of the first handful of Islamic banks, particularly in the decade of the seventies, led to the growth in the next decade of Islamic banks and banking all over the Muslim world. Today western economists are busy studying the potential impact of Islamic banking on economic relationships, as well as some of those aspects of Islamic banking which have met with success and show promise as profitable alternatives to established norms.

In the coming stages the work of economic historians will become increasingly important as their studies begin to inform the thinking of both Muslim economists and jurists, further increasing the complexity of the interdisciplinary mix, and further emphasizing the inadequacy of present classifications to encompass this fascinating new field. No doubt, the economic history of Muslims is fraught with lacunae; and there is much in our past that may be of relevance to the economic activity of our future. In particular, the ways in which Muslim scholars, especially the jurists among them, wrestled with problems of credit, trade, and production in the centuries prior to the depredations of the colonial powers may have much to tell us about how these issues may be dealt with today. Until recently, this has been a subject that failed to gain the attention of modern Muslim jurists, owing perhaps to their preoccupation with the classical period and its texts, so that many legal scholars remain in the dark with regard to the practices and strategies developed in the recent legal past.

Indeed, the point has been made, and it seems a valid one, that we are dealing with an interrupted process. Between the “medieval” and “modern” forms of Islamic banking transactions, as described by Nicholas Ray in his work on Islamic Banking, there lies a historical hiatus of as yet undetermined proportions and significance.

The areas of chief concern in the operations of Islamic Banks at present have been identified as trade financing and participatory or investment financing; the fatawa relevant to the three particularly Islamic modes of finance which represent the basis for, and majority of, operations within Islamic Banks are murabaha, mudarabah, and musharakah, each of which is used for investing. Murabaha, a form of trade financing, represents the most widely used of the three, yet the most suspect from an Islamic legal perspective. The other two operations are in no wise controversial, and musharakah may be understood to correspond to private investment funds, and mudarabah to public joint investment funds.

Extract from Translator's Introduction - Volume II

Leasing operations continue to be one of the mainstays of all Islamic banking and finance. Moreover, ijarah, like its three uniquely Islamic counterparts, murabaha, mudarabah, and musharakah, is essentially a contract developed in the classical period (i.e., the first four hijrah centuries). With the passage of time, however, and the changing of circumstances, these contracts have taken on refinements as Muslim scholars and investors have found ways to expand the utility of the contracts.

It can never be emphasized enough that Islamic law or fiqh is a process and not a code. Differences within and between legal schools of thought are often the blocks upon which lasting edifices may be built. In the short run, however, such differences may appear to represent serious obstacles to progress. The encouraging thing about contemporary Islamic banking and finance is that the will exists to overcome all such obstacles. Thus, today religious scholars, bankers, economists, lawyers, and financial experts are working together to develop products and services that both satisfy the needs of their clients and institutions, and at the same time comply with the moral and legal teachings of the Islamic faith. Perhaps even more encouraging is the interest and cooperation of experts who may not necessarily profess the Muslim faith, but whose efforts and diligence for the success of the new Islamic financial enterprise are equalled only by the most zealous of Muslims.

Several of the fatwas are quite innovative in their treatment of questions and to deal with the problem at hand in light of the changed circumstances, this is a situation that was not imagined in the experience of the classical jurists. This and several other such fatwas are indicative of an acceptance on the part of Shari'ah Supervisory Boards of new realities in the marketplace and of their willingness to understand and work with these to the extent that Islamic religious and legal principles will allow. Such an attitude has ever characterized the best in Islamic legal thought

These fatwas will probably mean little to those who have not previously acquainted themselves with the basic principles of the contracts represented.

For many the treatment of the subject matter of riba presents a real challenge on both a theoretical and a practical level. The concept requires a greater understanding and appreciation of riba as a prohibited element in Shari'ah compliant contracts and exchanges, as well as on Leasing and Exchange.

Extract from Translator's Introduction - Volume III

Wakalah (agency), kafalah (surety), rahn (collateral), and takaful (insurance) are integral elements of modern banking involving guarantee and commitment business, and are therefore closely interrelated subjects with particular interest to those laboring to provide an authentic Islamic alternative to “commercial insurance” (as it is termed in this volume). Indeed, while Islamic banking has enjoyed considerable growth and success, there are several sectors into which new Islamic financial alternatives have only now begun to make inroads. It is the hope of many that before long Muslims the world over will have access to all of the new Islamic alternatives to conventional, riba-based or riba ta¬inted, financial products.

Of key importance to any new undertaking is the matter of consumer trust. This is especially true in regard to Islamic financial products and needs bearing in mind by every Islamic financial operation. In its formal opinion on the issue of bank deposits, the Islamic Fiqh Academy of the organization of the Islamic Conference (97/3/90 of 1995), wrote:

The foundations of lawful dealings are trust and truth [that are] achieved by openly reporting facts in a way that dispels all confusion and ambiguity, accords with reality, and harmonizes with the Shari'ah perspective. This is especially important for [Islamic] banks in relation to the accounts they hold because their business is directly related to the need for trust, and because they must dispel ambiguity for everyone concerned.